For Warren Jabali: A Tribute to a Great Player

by Dave Thomas

dtec@cox.net

I played against Warren Jabali (formally Warren Armstrong) in high school. He was the greatest high school basketball player any of us had ever seen. This was Kansas City, Missouri in 1963 and ‘64 and some of the best high school basketball in the country was being played there. Lucius Allen was across the river in Kansas City, Kansas. Jo Jo White came up from St. Louis for the state tournament. Other remarkable players went on to have solid college careers, even pro careers, but the best--and everyone knew it--was Warren Jabali.

Here are excerpts from the Kansas City Star’s coverage of the 1963 Missouri State Basketball Tournament:

| Armstrong, opening with a flash of brilliance, turned friend and foe alike goggle-eyed as he rebounded, blocked shots and funneled in 26 points on his own.

Then Armstrong scored on a tip-in, stole the ball and stuffed in a 2-hand dunk shot that almost pulled the basket off the backboard.

Armstrong now has pumped in 87 points in his last three games, and it was his 17 points in the first half that got the Eagles off and flying.

With apologies to the ones I didn’t see, the best all-around players I saw were Warren Armstrong of Kansas City Central in Class L, . . . only a junior, Armstrong faces a great future if he consistently exercises all his tremendous talents. |

|

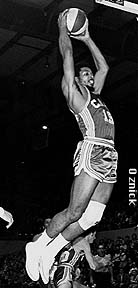

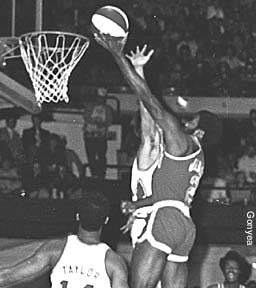

It’s important to remember that Jabali was only 6’2". Important also to remember that he could fly, really fly--a fact not known by those who came late to the ABA. I once saw him graze his forehead along the rim. It occurred in that same state tournament, following a very slick steal and in the middle of a slam dunk that brought everyone to their feet. It was an electrifying time. Legendary. In Kansas City--to this day, among men of a certain age--black and white--there is a bond because of it.

Jabali went on to set rebounding and assist records at Wichita State and was, at the time, their fourth all-time scorer. His senior year, Wichita State was considered to have the most difficult schedule of any college team in the country. Still, it was Wichita State. Had Jabali gone to Kansas or UCLA, he would not have been--or be today--so little known.

Following his senior year, Jabali signed with the Oakland Oaks in the ABA for what was even then a modest amount. The first thing he did with his signing bonus, his mother told me, was to free his father from one of the two jobs he had held for years.

His first season in the ABA, Jabali won Rookie of the Year honors. Here is what Rick Barry, his teammate, said about him:

|

| "He’s unbelievable. As a guard, he’s in a class by himself. I’ve never seen a player his size with so much strength. As great as Oscar Robertson is, well, he couldn’t come close to matching Armstrong in jumping and rebounding. Nobody can. He can out-jump and out-score the Warriors’ Al Attles. He’s stronger than I am; stronger than Robertson. He’s so powerful that even at 6’2", he can come in and rebound with 6’7" forwards. And you should see him drive into the basket. No doubt he’s one of the best guards I’ve ever played with--or against. Just wait till he gets more experience--nobody will be able to stop him." |

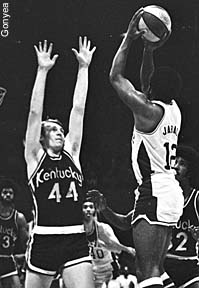

It was an injury to his back and another to his knee that stopped Jabali, or at least slowed, and lowered, his high-wire act. Even so, he exerted a commanding presence. His fifth year in the league he was voted "Most Valuable Player" in the All-Star Game held in Salt Lake City, a game that included Julius Erving, George McGinnis, and Artis Gilmore. That same year he was First Team All-ABA Guard and later, Alex Hannum called him "the smartest player I ever coached."

I lived in Denver when Jabali played for the Rockets and went to nearly every game. It was a great time for me, watching Jabali do what I felt he had always done; control and direct the game. He knew where to stand and what to do. The game flowed from him and through him as he interacted creatively with it (much like Larry Bird later would do) and for that reason alone he remained (at least for me) the most fascinating player by far to watch.

I lived in Denver when Jabali played for the Rockets and went to nearly every game. It was a great time for me, watching Jabali do what I felt he had always done; control and direct the game. He knew where to stand and what to do. The game flowed from him and through him as he interacted creatively with it (much like Larry Bird later would do) and for that reason alone he remained (at least for me) the most fascinating player by far to watch.

Once, in a very close game against my high school team, Jabali made a beautiful 30 foot jump shot, giving his team a lead they held to the end. When he made the shot I heard my coach disgrace himself by calling Jabali a freak. Jabali was anything but a freak. He was the star of the show. When the Denver Rockets had "Halter-Top Night"-- yes, that’s right, Halter-Top Night!, the two winners ("Best Halter-Top Outfit" and "Best Looking Girl in a Halter Top") were asked to name their favorite Rocket. Both answered, "Warren Jabali."

And yet, for all of this, there was apparently another side. I do not know the details surrounding the Jim Jarvis incident nor have I ever seen the tape. I did see Jabali’s temper on two occasions, once in high school in response to a series of intentional fouls, and once with the Rockets in response to a hard elbow to the lower back. On both occasions, he stopped short of anything that would have removed him from the game.

He was tough, no question about that, and strong, and proud; and he had a remarkable presence. In high school we sometimes remarked on how everyone in the league--or so it seemed--walked like Warren Armstrong. But even there--despite ourselves--we were on to something; walking--one of the four "dignities of man". And Jabali did have dignity. He may have lost it on occasion. The Jim Jarvis incident may be something he deeply regrets. I do not know. But for him to be remembered as a thug seems way off to me. I never saw a single incident in his two years as a Rocket that would justify such a label. Indeed, I saw quite the opposite.

Nevertheless, after his most effective year as a pro, his last season with the Rockets, he was released and not a single team picked him up. He was an unemployed All-Star guard. Of course, he also had been the player’s representative and had led the black players' boycott of a recent All-Star Game. He did have a reputation as a militant and he no doubt did champion unpopular views. It’s also the case that the Denver franchise was in trouble and even Larry Brown was quoted in one newspaper report as saying that Jabali had been made the scapegoat. I do not know the whole story. I do believe, however, that whatever the story, the truth itself was served by another of Brown’s comments (from the same report): "Warren has . . . never been hesitant about expressing himself," said Brown. "But he’s a person of high ideals, and an unselfish, dedicated basketball player."

Nine months after his release from Denver, Jabali was picked up by the San Diego Conquistadors with whom he played out the season, the last season of the ABA. Shortly after his arrival, Alex Groza, the San Diego coach said, "One guy has made a difference in this team. Warren is a very smart basketball player. He never gets excited, keeps his cool and helps out the other guys." Said back court partner, Bo Lamar: "This is a different team. Warren has made a big difference. . . . every team has a leader. But before we got Jabali, I don’t think this team had one. . . . I think he inspires the rest of us and gives us confidence."

Nine months after his release from Denver, Jabali was picked up by the San Diego Conquistadors with whom he played out the season, the last season of the ABA. Shortly after his arrival, Alex Groza, the San Diego coach said, "One guy has made a difference in this team. Warren is a very smart basketball player. He never gets excited, keeps his cool and helps out the other guys." Said back court partner, Bo Lamar: "This is a different team. Warren has made a big difference. . . . every team has a leader. But before we got Jabali, I don’t think this team had one. . . . I think he inspires the rest of us and gives us confidence."

This, I think, is what Jabali did from very early on. He played smartly, with cool, and always for keeps; and he inspired others, often with spectacular play. For many of us in the Kansas City area, he represented the first time we had seen such a gift. It was genius, foreshadowing what we later would see in a host of players who now are the new standard. Had it not been for injuries to his back and knee, had it not been for the politics of the time, had it not been for the specific requirements of his own development as a person--whatever they were, many more people would have had the pleasure of watching a truly gifted and remarkable player. As it was, many did see him play, and many of these, myself included, were enriched by it.

I believe--like most everyone I know--that if you are given a talent, then you must use it. There may be exceptions to this but on the whole I believe it is so, even though you may never know the good that comes from it. A great talent, like the one Jabali was given, may excite and entertain, it almost always does, but it also does more. Invariably, it leads the viewer to reflection and self-review. "What is my gift?" asks the person who is conscious of what he is seeing, and "How in the world can I bring it out?" We were all better off in Kansas City for having witnessed the great early--and then later--years of Jabali’s career; his brilliance made better players of us all though the "games" we chose to play came to vary considerably. I do not know if Jabali ever knew of this, of how his great play, the expression of his remarkable gift, was also a community service, raising and expanding our standards and aspirations. Many of us, I am sure, were never consciously aware of it. But I deeply believe it is so.

In 1975, the Kansas City Star carried an article reviewing Jabali’s career. Jabali had been invited to speak in a newly built community center to the kids playing in the league that carried his name and the article quoted Jabali’s remarks.

| "Some of you probably saw the movie Super Fly," Jabali began, then fixed the attention of a few giggling boys in the corner of the gym. "I know you guys are gonna be hustlers and pimps. Black people have always been hustlers and pimps. But get out of there as soon as you can. You’ll get hurt, you’ll get killed. Take advantage of this building. I know everybody says, ‘When I was comin up’ but when I was comin up we didn’t have this. Use it, get some books in here and read. It’s going to be hard. It’s hard now. You can’t go down to Ford or General Motors and work, they’re laying off now. It’s hard on your parents and it’s gonna be hard on you." |

The writer of this article, who may never have seen Jabali play, closed the article by saying that there was more, in his view, to Warren Jabali that "a ball and an iron ring." He felt "the man had a gift."

It is now twenty-five years since that article was written, twenty-five years, or nearly so, since the ABA disbanded. I do not know what Jabali is doing. The last I heard he was teaching in an elementary school in Miami. If he is teaching, I wonder if the children with whom he now works, or his fellow teachers, or his own children for that matter, have any idea of the regard with which he is held in certain circles. In Kansas City, there is an entire cohort who speak of him with enormous respect. The mere mention of his name conjures a time that shines far more brightly because of his presence in it.

This brief tribute is a way of remembering, a way of saying thanks. Whatever Jabali is doing today, I hope it is something that allows his spirit to soar. He was something special. For many of us growing up in the Kansas City area, his play gave us a vision without which, I believe, we would have settled for less in ourselves. I thank him for that. He was a player’s player and by his play would-be players like myself were inspired out of our limits.

by David Thomas.

Comments to dtec@cox.net

POSTSCRIPT

In March of this year (‘98), the Kansas City Star ran an article examining an issue of considerable importance (judging from the reaction it generated) to area basketball fans; namely, who was the greatest player ever to come out of the Kansas City area. The major contenders were Jabali (Warren Armstrong), Lucius Allen, Anthony Peeler and a young player graduating from high school this year (and hence the reason for the article), JaRon Rush.

Here are a few quotes from the article:

"Many of the people who saw all four wouldn’t necessarily admit it, but they sounded as if they’d give a slight edge to Armstrong, a dominant force at Central in the early 1960’s."

"I played against Elvin Hayes and Don Chaney in college, but Warren was better then them," said Mike Thiessen, a first-team All-Metro selection . . . in 1965. "He did things in high school that Michael Jordan does now."

"Warren and Lucius Allen played the best competition. JaRon hasn’t been challenged like that. I haven’t seen JaRon play this year, but I don’t think he’s in the same league as (Armstrong). Warren had a court sense that was scary. He had a soft touch and could jump over the backboard. As good as JaRon is, he isn’t in the same league as far as being a complete basketball player. He doesn’t play defense like Armstrong and Allen did."

"He (Armstrong) was a man among boys," (Charles) Weems (a former official) said. "You knew what he was going to do, but you couldn’t stop him. I always felt like he was two steps ahead of everybody."

"He (Peeler) had eyes in the back of his head," said Central coach Jack Bush, . . . "Peeler could pass . . . He could thread a needle from 50 yards. But Warren Armstrong had wings. He’d jump up and dunk off a missed rebound from the second block."

"Armstrong was like Julius Erving," (said former Rockhurst High coach Graig Cummings). "There wasn’t a term yet for some of his dunks. But JaRon might be the most complete player of them all. He handles the ball, shoots and, when he wants, plays outstanding defense. But Warren just could do things beyond anybody else. He might have been the best."

|

In late May, two months after the article appeared, I received from Jabali a copy of a letter that several weeks earlier he had sent to the KC Star. I found the letter powerful and moving, to say the least, and certainly deserving of a much wider audience than it had received to date. I therefore asked Jabali for his permission to reprint the letter here. For whatever reason, the KC Star has yet to print it:

GREATEST HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETE: A REPRISE

In 1964, the year in which I graduated from Central High School, an article ran in the Kansas City Star which I have kept until this day. The article was written by a man whom I had never met, nor had any subsequent contact with. The article was stirring but I was for the most part oblivious to its deeper meaning. I knew intrinsically that it was important but I could not accurately interpret its message at the time. I eventually came to realize the depth of admiration, respect and hope which encompassed his words - and the onus.

Life as it unceasingly does, has come full circle. I now have the opportunity, privilege and duty to speak about a young man with great potential who has been given the designation of "greatest high school basketball player" in the Kansas City area. The author of the 1964 article who assumed me that position, pointed out that with the passage of time we see an improvement in the quality of players. I therefore have no doubt that JaRon Rush has superior basketball skills than Lucius Allen and myself. However, skills alone do not result in ultimate success. If the concession is made that I was more skilled than Lucius, how then should that concession be impacted by the facts that Lucius enrolled and graduated from a better university, made the college All America team and played in the dominant league. Meanwhile, I with the "superior skills" never matched his accomplishments.

I would submit that great skill, if it is to be actualized, must be combined with maturity of intellect, social development and morality. Therein lies the problem. The average 17 year old person has not yet developed sufficient measures of intelligence, morality and social skills and is therefore compelled to make decisions impulsively. The 17 year old super athlete, while usually ordinary in intellectual and spiritual maturity, is confronted with extraordinary options which must be acted upon. These options, once decided upon, translate into extraordinary responsibilities. As a consequence of bearing such responsibilities, young people frequently find themselves "bent out of shape".

In any of the world’s scriptures we can find the advice to seek wisdom. This is especially important for young people who have such responsibilities. Since it is foolishness which abounds in the hearts of the young, it is prudent for them to seek counsel. The decision as to who is to provide counsel is crucial. Parents are generally best qualified to operate in this role. It is no accident that Kobe Bryant is having a successful career so far. He clearly accepts the guidance of his parents. His parents however are completely qualified for the role since his father is a former longtime professional basketball player himself and his mother a college trained professional There are occasions when parents may not have the exposure themselves to assist in the decision-making process. My parents could not aid me in making my decisions because I was involved in issues which were beyond their areas of expertise. Parents must be careful not to over extend themselves. Players themselves must feel that their choice of college and any subsequent contracts are in their best interest or they will be unable to sustain the proper attitude with which to attain their full potential.

The key to greatness in my opinion is the ability to freely express one’s gift. One’s talent must flow as a direct and uninhibited stream which seeks and finds its own level. Things which inhibit the free flow of talent are not being coachable, not maintaining optimum conditioning, a lack of leadership skills and selfishness. The item selfishness may seem out of place, however a review of all truly great players will reveal that they always made everyone around them better. Kareem Abdul Jabbar did not win an NBA championship until Oscar Robertson (the man who averaged triple doubles for a whole year) joined him in Milwaukee and he did not win another until Magic Johnson joined with him in Los Angeles. These players brought out the best in each other. Greatness requires commitment, dedication and teamwork.

The writer of the 1964 article which challenged me to strive for athletic greatness also "urged" me to be an example for my race. I have no way to know how he would view my accomplishments on these two fronts. I sincerely hope that he would be pleased. My own opinion on the subject is that I became a good player and not a great player. Factors for not being better were injuries to my knee and back. Another factor was that I never considered sport as a higher priority than the struggle of African American People to gain standing in the human community.

That struggle remains a focus of my energies today. It is paradoxical that in spite of the spectacular achievements of African Americans, the race as a whole is actually worse off than it was 34 years ago when I left Kansas City. For example, in 1964, a significant percentage of the African American population lived below the poverty line, were unemployed, under-educated and segregated. In 1998, there are still significant percentages of impoverished, unemployed, under-educated and segregated African Americans. 1998 is worse than 1964 because in 1964 we had more stable neighborhoods, we had a movement and we had hope. We had an agreed upon enemy, which we identified as racism and we had clear purpose in mind. In 1998 we have an expanding underclass, drug and crime infested neighborhoods, mounting numbers of out of wedlock children being born to teenagers, an appalling lack of interest in education in light of the monumental struggles and disillusionment in the ranks of upwardly mobile African Americans. In 1964, the music, always an accurate reflection of culture, promoted unity and struggle. Curtis Mayfield sang "Keep On Pushing" and "We’re a Winner". James Brown sang "I’m Black and I’m Proud". In 1998, Ice Cube represents by singing "Today Was a Good Day, I Didn’t Even Have To Use My AK".

The "Talented Tenth" (the most well to do African Americans) which W.E.B. DuBois theorized would lead and uplift the race has in fact detached and abandoned the race. It may be that Gil Scott Heron, who also sang in the 60’s was prophetic with his lyrics, "It’s winter in America . . . All of the healers have been killed, sent away and betrayed . . . And ain’t nobody fighting, cause nobody knows what to save".

As a result of all this, I am not at all certain whether the "race" baton which was passed to me, can be now passed to JaRon. But, someone else sang a long time ago and they sang that "The Darkest Hour is Just Before Dawn", and therefore I choose to be optimistic. I choose to believe that African Americans will eventually develop as a people and address our own problems. I choose to believe that young men like JaRon, who most likely will soon join a growing fraternity of African American multi-millionaires, will figure out some way to serve and profit from development in their own communities. I have hope that Florida A&M University (FAMU), a predominantly Black institution which has a business school which ranks in the top 2 percent in the country (this is a ranking of all schools, not just Black schools) will recognize its potential. FAMU currently trains its business students for "employment" in the corporate world as opposed to training in the creation of corporations. Perhaps one day the athletes will sit down with the business majors to create the ways and means for African American participation in the economic mainstream. Such is the nature of my faith.

At this moment, none of this should be the focus for JaRon. He should be preparing to embark upon a great adventure. The most important thing for him is to enjoy and appreciate the blessings which will result from his gift. Involvement in social affairs may result from this appreciation. JaRon himself will determine how he is to pay his dues to the creator for giving him the potential to have such a wonderful life.

Warren Jabali (a.k.a. Warren Armstrong)

Miami, Florida

1998

|